Tu carro esta vacío

How Do Iris Patterns Form?

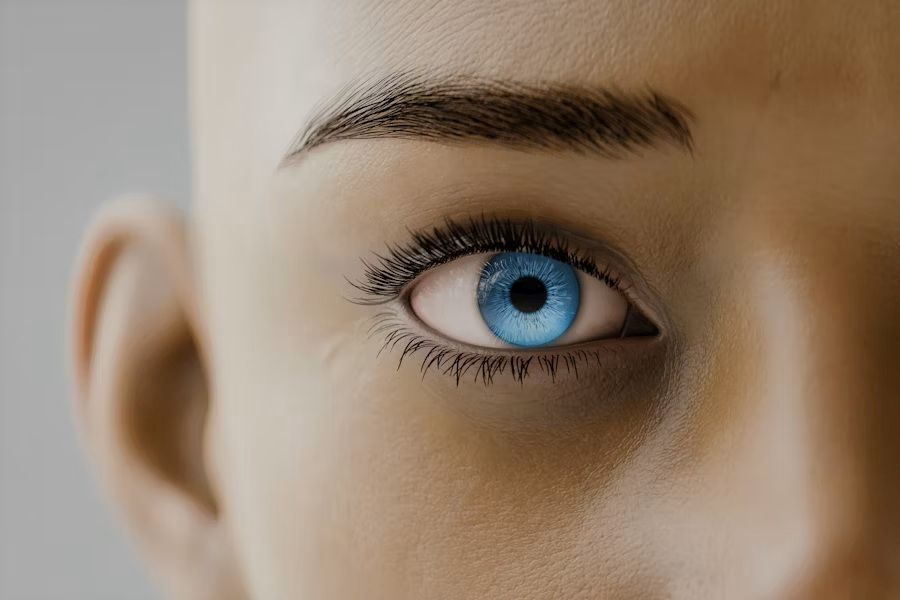

When you look into someone's eyes, you're witnessing one of nature's most intricate designs. The colored part of our eye—the iris—contains patterns as unique as fingerprints. These delicate structures not only give our eyes their distinctive appearance but also serve crucial biological functions. The formation of iris patterns represents a remarkable intersection of genetics, development, and individual uniqueness that begins before birth and continues to evolve throughout our lives.

The Fascinating Structure of the Iris

The iris is the colored ring surrounding your pupil that controls how much light enters your eye. This seemingly simple structure is actually a complex arrangement of connective tissue, pigment cells, muscle fibers, and blood vessels.

The iris contains two main muscle groups that work in opposition to each other. The sphincter muscle constricts the pupil in bright light, while the dilator muscle expands it in darkness. These muscles create many of the radial patterns we observe in iris structure.

Between these muscles lies the stroma—a layer of connective tissue containing blood vessels, pigment cells, and distinctive structural patterns. Beneath the stroma is the epithelium, which contains dense pigment cells that prevent light from entering the eye except through the pupil.

The surface features we recognize as iris patterns include:

-

Crypts: Pit-like depressions where the stroma tissue is thinner

-

Furrows: Circular or radial lines created by connective tissue folds

-

Collarette: The thickened ring dividing the pupillary and ciliary zones

-

Pigment spots: Concentrated areas of melanin that appear as freckles

Embryonic Development: Where Iris Patterns Begin

The formation of iris patterns starts remarkably early in our development. By the third month of gestation, the basic structure of the eye is already taking shape. The iris begins as a simple sheet of tissue that must transform into a complex, functioning structure through a process called morphogenesis.

Around the sixth month of pregnancy, a critical event occurs—the pupillary membrane (a layer of tissue covering the developing iris) begins to deteriorate. This deterioration doesn't happen uniformly, creating the first variations in the iris's surface.

Simultaneously, the mesenchymal cells that will form the stroma begin migrating and arranging themselves into unique patterns. This process is influenced by a combination of genetic instructions and random cellular movements. The developing iris undergoes waves of cell death and proliferation, further contributing to its distinctive appearance.

By birth, the basic pattern structure is established, though the color typically develops over the first few years of life as melanin production increases.

The Genetic Blueprint of Your Iris

Your iris pattern is predominantly determined by your genetic code, yet in a fascinatingly complex way. Unlike traits that follow simple inheritance patterns, iris structure is polygenic—controlled by multiple genes working in concert.

These genes control:

-

The density and distribution of melanin (affecting color)

-

The thickness and arrangement of stromal fibers

-

The development of crypts, furrows, and other structural features

-

The balance between various tissue types within the iris

What makes iris patterns unique is that while genes provide the blueprint, the actual formation involves chaotic processes. The final arrangement of iris features resembles what scientists call a "chaotic system"—deterministic but inherently unpredictable in its exact outcome.

This combination of genetic influence and developmental chaos explains why even identical twins, who share the same DNA, have distinctive iris patterns. Each iris forms through a slightly different developmental journey, resulting in a unique structural fingerprint.

The Science of Iris Color

While iris patterns form through structural development, iris color is determined by pigmentation—specifically, the amount and distribution of melanin in the iris tissue. The fascinating aspect of iris color is that it involves not just pigment quantity but also how that pigment is scattered and reflected through the iris's complex structure.

In blue eyes, the stroma contains relatively little melanin. The shorter blue wavelengths of light scatter more readily (the same Rayleigh scattering phenomenon that makes the sky appear blue), creating the blue appearance.

Green and hazel eyes contain moderate amounts of melanin in the stroma, combined with the light-scattering properties of the iris structure. Brown eyes have abundant melanin in both the stroma and epithelium, absorbing most light and appearing darker.

The genes governing iris color interact with those controlling structural patterns. This interaction contributes to the tremendous diversity in human eye appearance, from the distribution of pigment to the visibility of structural features like crypts and furrows.

Why Every Iris is Unique: The Biometric Perspective

The uniqueness of iris patterns makes them ideal for biometric identification. Each iris contains approximately 200 distinct structural features that can be mapped and quantified, creating a "fingerprint" with extraordinary specificity.

This uniqueness stems from several factors:

-

The chaotic nature of embryonic development that creates unpredictable patterns

-

The high number of independent features that can vary between individuals

-

The genetic complexity controlling iris formation

-

Environmental factors during development that influence final outcomes

The probability of two irises being identical is estimated at 1 in 10^78—far exceeding the number of humans who have ever lived. Even more remarkably, the right and left irises of the same person have completely different patterns, despite sharing the same genetic blueprint.

This unparalleled uniqueness makes iris recognition technology exceptionally reliable, with error rates significantly lower than other biometric methods like fingerprinting or facial recognition.

Changes in Iris Patterns Throughout Life

While the basic structure of your iris is established before birth, it doesn't remain static throughout your lifetime. Iris patterns undergo subtle changes as you age, though the core pattern remains stable enough for long-term identification.

In infancy, melanin production increases, potentially changing eye color (particularly in those of European descent, who often have light blue eyes at birth). During childhood and adolescence, the iris patterns stabilize but may show minor adjustments as the eye grows.

In adulthood, several factors can modify iris appearance:

-

Medical conditions affecting eye pressure or inflammation

-

Prolonged medication use (some drugs can alter iris color)

-

Exposure to UV radiation, which may increase pigmentation

-

Age-related thinning of iris tissue, making some features more prominent

These changes typically affect color more than pattern, which is why iris scans remain reliable for identification over decades. The connective tissue architecture—the furrows, crypts, and collarette—maintains remarkable stability throughout life.

The Extraordinary Complexity Behind Eye Patterns

The formation of iris patterns represents one of the most visually striking examples of biological complexity in the human body. What appears as a simple colored ring to the casual observer reveals itself as an intricate landscape shaped by genetics, development, and chance.

The study of how iris patterns form bridges multiple scientific disciplines, from embryology and genetics to optics and biometrics. This intersection of fields continues to yield new insights into human development and the beautiful diversity of our appearance.

Next time you look into someone's eyes—or your own in the mirror—take a moment to appreciate the extraordinary developmental journey that created those unique patterns. Your iris represents a biological signature that began forming before you were born, one that combines genetic inheritance with the unrepeatable circumstances of your development.

In those delicate swirls, lines, and dots lies not just your visual identity but a record of one of nature's most remarkable processes of pattern formation.

Deja un comentario

Los comentarios serán aprobados antes de aparecer.